Teaching Kids Responsibility (Without Constant Reminding)

The key to raising responsible kids isn't reminding them more—it's building systems that let them remember themselves.

Long story short

- Constant reminding prevents kids from developing organizational skills

- External motivation (reminders) doesn't build lasting habits—internal motivation does

- Visible systems (checklists, charts, calendars) let kids manage themselves

- Step back and allow some failure—natural consequences are the best teachers

- The goal isn't perfection, it's raising kids who can manage their own responsibilities

"Did you pack your lunch?"

"Did you finish your homework?"

"Did you remember your gym bag?"

"Did you brush your teeth?"

If you're a parent, you've probably said some version of these sentences hundreds of times. Maybe thousands.

The intention is good: you want to help your child succeed. But constant reminding creates a problem. The child learns to rely on the reminder instead of developing their own memory and organization skills. And you become exhausted from being a human task manager.

There's a better way.

The Reminder Trap

Reminding feels helpful in the moment. It prevents immediate failures—the forgotten lunch, the undone homework, the missed deadline.

But it comes with hidden costs:

- It prevents learning. When we shield children from the natural consequences of forgetting, we remove their motivation to remember. Why develop organizational skills when mom or dad will always catch things?

- It breeds dependency. Kids learn that they don't need to track their own responsibilities—someone else will do it for them. This dependency can persist into adulthood.

- It damages relationships. Constant reminding feels like nagging, to both parties. It creates a dynamic of parent-as-supervisor and child-as-supervised, rather than a relationship of growing autonomy.

- It exhausts parents. Keeping everyone else's responsibilities in your head is mentally draining. It's the "mental load" that falls disproportionately on certain family members.

The alternative isn't neglect. It's systems—structures that help children manage their responsibilities themselves.

External vs. Internal Motivation

Understanding motivation helps explain why reminding backfires.

- External motivation comes from outside—rewards, punishments, or in this case, reminders. It works in the short term but doesn't build lasting habits.

- Internal motivation comes from within—satisfaction in accomplishment, desire to be capable, personal investment in the outcome.

When a parent constantly reminds, the motivation stays external. The child does the task because they were reminded, not because they've internalized the responsibility.

When a child uses a system to remember—checking their own list, following their own routine—the locus of control shifts. They're managing themselves. The satisfaction of checking off tasks becomes its own reward.

This doesn't happen overnight. It requires scaffolding: providing the systems and structure that enable self-management, then stepping back to let the child use them.

Age-Appropriate Responsibilities

What children can be responsible for varies by developmental stage.

Ages 3-5

- Putting toys away (with specific homes for each type)

- Putting dirty clothes in hamper

- Simple self-care (washing hands, brushing teeth with supervision)

- Clearing their plate after meals

- Feeding pets (with supervision)

At this age, routines matter more than independent decision-making. The goal is building habits through consistent sequences.

Ages 6-9

- Making bed

- Getting dressed independently

- Packing school bag (with checklist)

- Homework without prompting

- Simple chores (setting table, emptying wastebaskets)

- Managing own belongings

This is when visible systems become crucial. A child who can read can follow a checklist. A routine displayed on the wall can guide morning preparation without verbal reminding.

Ages 10-12

- Complete homework management

- Managing their own schedule

- Laundry (washing, folding, putting away)

- Preparing simple meals

- Caring for younger siblings for short periods

- Managing money (allowance, saving for wants)

At this stage, parents should be coaches more than managers. Check in periodically, but let the child handle day-to-day execution.

Ages 13+

- Full responsibility for academics

- Managing commitments and schedule

- Contributing meaningfully to household work

- Part-time job or regular volunteer work

- Increasing financial independence

Teens should be running their own lives, with parents as safety net and advisors rather than managers.

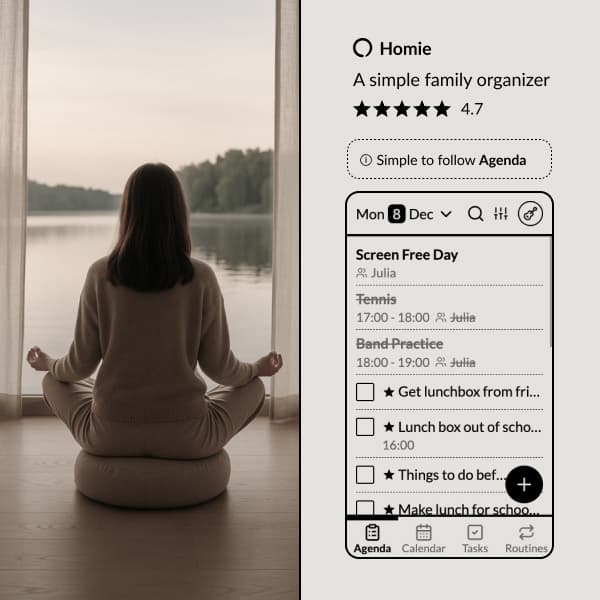

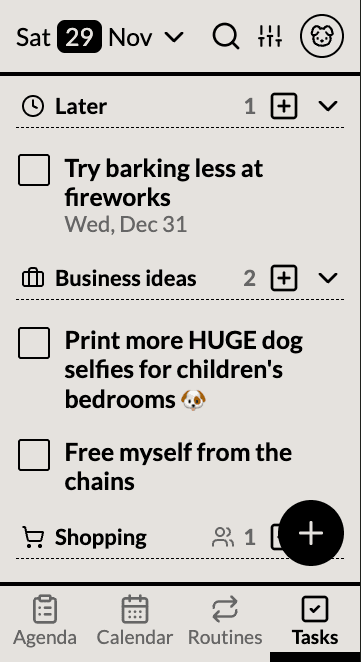

The Power of Visible Systems

The single most effective tool for building responsibility is making expectations visible.

When responsibilities live only in a parent's head, communication requires constant talking—which sounds like nagging. When responsibilities are displayed where everyone can see them, communication is built into the environment.

- Chore charts work. Simple as they are, a chart showing who does what makes responsibilities clear and eliminates the "I didn't know I was supposed to" excuse.

- Checklists work. A morning routine checklist, a "before leaving for school" checklist, a bedtime checklist. Kids can check their own completion without being asked.

- Family calendars work. When everyone's activities and responsibilities are visible in one place, coordination happens naturally.

The medium matters less than the visibility. A paper chart on the fridge works. A whiteboard in the hallway works. Homie on a mounted tablet works. What matters is that information is always there, always visible, not requiring anyone to ask or remind.

Here's how we've solved it in the Homie app:

with simple sharing to get things done.

Organize tasks into lists that you can optionally share with other users.

Subtasks to break down big tasks into manageable steps.

Notifications for important tasks.

Share links to task lists and allow anyone to collaborate, even without a Homie account.

How to Step Back

Building systems is the first step. The harder step is actually stepping back and letting the child use them.

This means tolerating some failure. When your child forgets their lunch despite having a checklist, the natural consequence (being hungry, having to buy lunch, explaining to a teacher) teaches more than any reminder could.

- Start with low-stakes responsibilities. Let them fail at things that won't have lasting consequences. Forgetting a library book teaches the same lessons as forgetting important homework, with less fallout.

- Warn once, then stop. "This is what your checklist is for" is reasonable. Repeating it every day is not. Say it once, then trust the system.

- Debrief after failures. When things go wrong, talk about it—not to scold, but to problem-solve. "What could help you remember next time?" Maybe the checklist needs adjustment. Maybe items need to be packed the night before. Let the child be part of the solution.

- Celebrate independence. Notice and name when your child manages something themselves. "I noticed you packed your bag without any reminders this week. That's really mature."

When Things Fall Apart

Even with good systems, kids will fail sometimes. This is normal and necessary.

What matters is how you respond:

- Don't rescue. When possible, let the natural consequence happen. Driving the forgotten item to school removes the consequence that teaches.

- Do distinguish between mistakes and patterns. Everyone forgets sometimes. That's different from consistently failing to use available systems. Occasional mistakes need grace; patterns need problem-solving.

- Do adjust systems that aren't working. If the same failure keeps happening, the system needs improvement—not just more reminding within the same broken system.

- Don't shame. "See, this is what happens when you don't listen to me" teaches nothing except that failure means parental disappointment. Better: "That must be frustrating. What do you think would help prevent this next time?"

A Real Example: Our Daughter

Our fourteen-year-old daughter has ADHD. Organization doesn't come naturally to her.

For years, we were the reminder system. "Did you check your schedule?" "Do you have your tennis racket?" "Is your homework done?" It was exhausting for us and didn't help her build skills.

What changed:

We set her up with her own Homie view showing her routines and calendar. Every morning and evening, her routines are right there—not on a phone mixed with other apps, but on a dedicated display she passes on her way out the door.

We stopped reminding. This was hard. Watching your kid head to school without something they need, when you know they need it, requires real restraint.

She failed a few times. Forgot her gym clothes. Missed a deadline. These weren't catastrophic, but they were uncomfortable enough to motivate change.

Now, she checks her own routine. She packs her bag the night before because she learned (the hard way) that morning packing leads to forgotten items. She owns her schedule because she's the one who has to live with the consequences of missing things.

She's not perfect. No one is. But she's managing herself in a way she never did when we were doing the managing for her.

The Goal Isn't Perfection

The goal isn't raising kids who never forget anything. The goal is raising kids who can manage their own responsibilities—including managing their own failures.

Adults forget things too. The difference is that capable adults have systems: calendars, lists, reminders, routines. They know how to set themselves up for success.

Teaching responsibility isn't about demanding perfection or removing every support. It's about shifting from parent-as-reminder-system to parent-as-system-builder.

Give them the tools. Show them how to use the tools. Then step back and let them use them—even when it's hard, even when they fail, even when part of you wants to jump in and rescue.

That's how children become capable adults. Not by being managed, but by learning to manage themselves.

Explore Homie

Mindfully designed for

SIMPLICITY

Ready to organize your family?

Try Homie free and see how simple family organization can be.