Why Writing Things Down Actually Reduces Stress (The Science)

Your brain doesn't know what day it is. Here's the psychology behind why getting tasks out of your head and into a system you trust can dramatically reduce your stress.

Long story short

- Your brain has no sense of time—tasks due tomorrow and next month feel equally urgent

- Incomplete tasks create psychological tension that persists until resolved (the Zeigarnik Effect, 1927)

- You don't have to complete a task to stop it intruding—just capture it in a system you trust

- Writing things down releases the tension and frees up mental space

- For families, a shared visible system means nobody has to be the "human calendar"

It's 3am. You're lying awake, and suddenly your brain reminds you: the birthday party is Saturday and you haven't bought a gift. Also, the dentist appointment needs rescheduling. And did anyone sign that permission slip?

None of these things need to happen right now. One is days away, one is weeks away, one can wait until morning. But your brain doesn't care. They all feel equally urgent, equally pressing, equally now.

This isn't a character flaw. It's how your brain works.

Your Brain Doesn't Have a Calendar

David Allen, author of Getting Things Done, puts it simply: "Your head's a really bad office because it doesn't have a sense of past or future."

This is the insight that changes everything.

When you make a commitment—even a vague one to yourself like "I should really clean out the garage someday"—your brain doesn't file it away under "someday." It holds onto it. And because your unconscious mind has no concept of time, that garage project sits alongside tonight's dinner and next month's school event, all demanding equal attention.

Allen calls these unfinished commitments "open loops." They occupy what he calls "psychic RAM"—the mental buffer where your brain holds everything it thinks you need to remember.

The problem? This buffer isn't very big. And every open loop takes up space, whether it's "buy milk" or "figure out career direction." Your brain treats them all with the same urgency because, to your unconscious mind, they're all happening right now.

The Waiter's Paradox

In 1927, a Lithuanian psychologist named Bluma Zeigarnik noticed something strange while sitting in a Vienna café.

The waiters had remarkable memory for open tabs—they could recall complex orders across multiple tables without writing anything down. But as soon as a bill was paid, they couldn't remember what had been ordered. The information just... vanished.

Zeigarnik went on to study this phenomenon in her laboratory. She gave subjects a series of simple tasks—puzzles, arithmetic problems, small crafts—but interrupted them before they could finish half of them. Later, when asked to recall the tasks, subjects remembered the incomplete ones at nearly twice the rate of the completed ones.

This became known as the Zeigarnik Effect: incomplete tasks persist in our memory, creating a kind of psychological tension that keeps them top of mind.

The brain does this for a good reason—it wants you to finish what you started. But in modern life, where we have dozens or hundreds of incomplete tasks at any given moment, this feature becomes a bug. Instead of helpful reminders, we get a constant background hum of anxiety.

The Tension That Never Releases

Here's what the Zeigarnik Effect means in practice:

Every task you've started but not finished—every commitment you've made but not kept—every "I should really..." that's floating in your head—creates psychological tension. Your brain keeps returning to these open loops, trying to push you toward completion.

But you can't complete everything at once. So the tension builds. The loops multiply. And you end up with that vague, persistent feeling that there's always something you should be doing, something you're forgetting, something that needs your attention.

This isn't laziness or poor time management. It's your brain working exactly as designed, but overwhelmed by the sheer number of commitments modern life generates.

Research has shown that this tension from unfinished tasks correlates with higher stress, difficulty sleeping, trouble concentrating, and reduced performance on other work. The open loops don't just sit quietly in the background—they actively interfere with your ability to focus on what's in front of you.

The Breakthrough: You Don't Have to Finish—Just Plan

Here's where the science gets really interesting.

In 2011, researchers E.J. Masicampo and Roy Baumeister published a study in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology that challenged everything we thought we knew about the Zeigarnik Effect.

Their question was simple: Does the psychological tension from an incomplete task persist until the task is done, or can something else release it?

Across multiple experiments, they found that unfulfilled goals caused intrusive thoughts that interfered with unrelated tasks. No surprise there—that's the Zeigarnik Effect in action.

But then they tried something different. They had participants make a specific plan for when and how they would complete the unfulfilled goal. Not complete it—just plan it.

The intrusive thoughts disappeared.

As they wrote: "Committing to a specific plan for a goal may therefore not only facilitate attainment of the goal but may also free cognitive resources for other pursuits."

This is the key insight: You don't have to finish a task to stop it from haunting you. You just have to capture it in a system you trust.

The Trusted System

This is the foundation of Allen's Getting Things Done methodology. The goal isn't superhuman productivity or inbox zero or getting more done. The goal is "mind like water"—a calm, clear mental state where you can respond appropriately to demands without overreacting.

How do you get there? By getting everything out of your head and into an external system. Allen explains:

"These open loops lurk in your subconscious mind, draining precious mental energies and preventing full effectiveness."

When you write something down in a system you trust—and this is the key part, trust—your brain can let go. The Baumeister research showed why: making a plan signals to your brain that this is handled, that future-you will deal with it at the appropriate time. The tension releases.

"A lot of people—that just sort of changes their life actually," Allen says. "When they just get into GTD, they just get this first stage and start writing down a lot more than they ever wrote down before, sleep better, able to focus better."

Not better task management. Not higher productivity. Just... less stress. Better sleep. More focus. Because the open loops finally closed.

Why This Matters More for Families

Here's where it gets personal.

If open loops create stress for individuals, families multiply the problem exponentially.

You're not just tracking your own commitments—you're tracking (or trying to track) the schedules, needs, and responsibilities of every person in your household. Soccer practice. Doctor appointments. Permission slips. Whose turn is it to walk the dog? Did anyone buy milk? Is Thursday a half-day?

When this information lives in one parent's head, that parent becomes the "default parent"—the family's human calendar, constantly processing, remembering, reminding. This creates exactly the psychological tension Zeigarnik described, but multiplied across an entire household's worth of commitments.

And when information is scattered—some in your head, some in your partner's head, some on the school calendar you keep forgetting to check—nothing feels fully captured. The loops stay open. The tension persists.

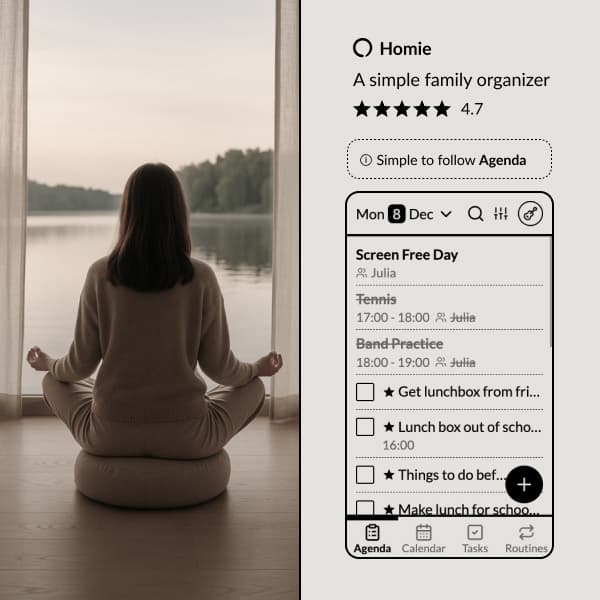

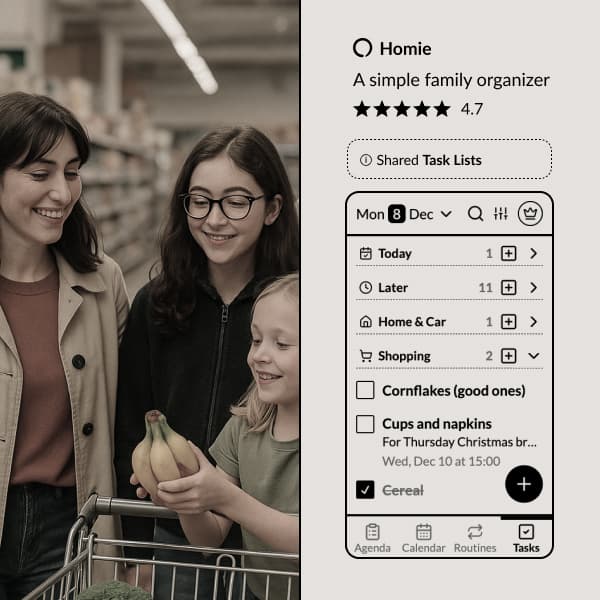

Making It Visible

The solution isn't just writing things down. It's creating a shared external system that everyone can see and trust.

When a family calendar lives on a tablet on the wall—not buried in someone's phone—it becomes ambient information. You don't have to remember to check it. It's just there, visible, updating your sense of "what's happening" without requiring mental effort.

When tasks have clear ownership and visibility, nobody has to hold the mental model of who's supposed to do what. The system holds it.

When routines are visible, kids can follow them without being reminded—which means parents don't have to hold "did they brush their teeth?" as an open loop.

This isn't about productivity. It's about distributed cognition—using the environment as external memory so your brain doesn't have to do all the work.

The Catch: You Have to Trust It

The Baumeister research revealed an important detail: the plan had to be earnest. Participants who didn't really intend to follow through still experienced intrusive thoughts.

The same applies to external systems. If you write something down but don't trust you'll actually see it again, your brain won't let go. If the family calendar exists but nobody checks it, it doesn't provide relief—it just becomes another place where things get lost.

This is why review matters. This is why visibility matters. This is why the system has to be simple enough that people actually use it.

A sophisticated app that nobody opens is worse than a paper calendar on the fridge that everyone sees.

Start Here

You don't need a perfect system. You don't need an app, a method, or a framework.

You need one thing: a place to capture what's in your head, that you trust you'll check again.

For some families, that's a shared calendar app. For others, it's a whiteboard by the front door. For us, it's Homie on a tablet mounted in the kitchen—visible to everyone, updated by everyone, trusted by everyone.

The specific tool matters less than the practice: get it out of your head and into a system you trust.

Your brain will thank you. Probably at 3am, when you're actually sleeping instead of remembering about that birthday gift.

References

- Allen, D. (2001). Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity. Penguin Books.

- Masicampo, E.J., & Baumeister, R.F. (2011). Consider It Done! Plan Making Can Eliminate the Cognitive Effects of Unfulfilled Goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

- Heylighen, F., & Vidal, C. (2008). Getting Things Done: The Science behind Stress-Free Productivity. Long Range Planning, 41(6), 585-605.

- Zeigarnik, B. (1927). Über das Behalten von erledigten und unerledigten Handlungen. Psychologische Forschung, 9, 1-85.

Explore Homie

Mindfully designed for

SIMPLICITY

Ready to organize your family?

Try Homie free and see how simple family organization can be.